Brian Cross photo

See Full Western Producer Article

https://www.producer.com/2019/02/seed-farm-built-on-hard-work-perseverance/

Jed and Kathy Williams, leafcutter bee and alfalfa seed producers from Imperial, Sask., stand in their warehouse that contains 9,000 nesting boards filled with bee larvae. This winter, the couple will extract more than 100 million larvae, which will be packaged and sold or incubated and used as pollinators on the Williams farm.

On the Farm: Sask. couple weathers downturn in alfalfa seed business while expanding their leafcutter bee operation

IMPERIAL, Sask. — Selling products into a niche agriculture market is often about risk and reward.

The rewards are obvious when market conditions are favourable and the risks become evident when supply and demand fundamentals take a turn in the wrong direction.

Alfalfa seed and leafcutter bee producers Jed and Kathy Williams from Imperial, Sask., know all about the pitfalls of operating in a niche market.

A few years back, North American demand for alfalfa seed and leafcutter bees was humming along nicely and the Williams were anticipating record sales of bee larvae and alfalfa seed

But then the market went south, forcing the couple to reassess their position and make some tough decisions.

Ultimately, they decided to forge ahead, make necessary adjustments and be prepared for a market rebound.

“Right now, the wholesale bulk market (for alfalfa seed) is terrible,” said Jed, who grew up on a sheep farm near Esperance, Western Australia.

“Two years ago, it was about $2.20 a pound … (off the combine). At the current time, it’s about 50 to 60 cents a pound.

“Today, it’s all about digging in with your teeth and nails and trying to hang on.”

Jed and Kathy are using determination, hard work and good management skills to weather the economic storm.

The couple met in Australia in the early 2000s.

At the time, Kathy, a farm girl from Imperial, Sask., was visiting Australia.

There she met Jed, who had moved from Esperance to the Australian state of Queensland on the opposite side of country.

Jed was in Queensland exploring opportunities in the Australian agriculture sector following a collapse in global wool markets that forced his family to sell its sheep operation.

The couple began dating, fell in love and when Kathy returned to Canada, Jed followed six months later.

“I came to Canada with a toolbox and a promise to marry a girl,” Jed said.

“But when I first came here in 2001, you could rent farmland at a reasonable price and you could still buy a cheap house.”

Today, Jed and Kathy have three children aged 12, 9 and 7.

Initially, they farmed with Kathy’s father but eventually decided to set out on their own.

They started small and expanded their alfalfa seed operation with the help of Jed’s income from a nearby potash mine.

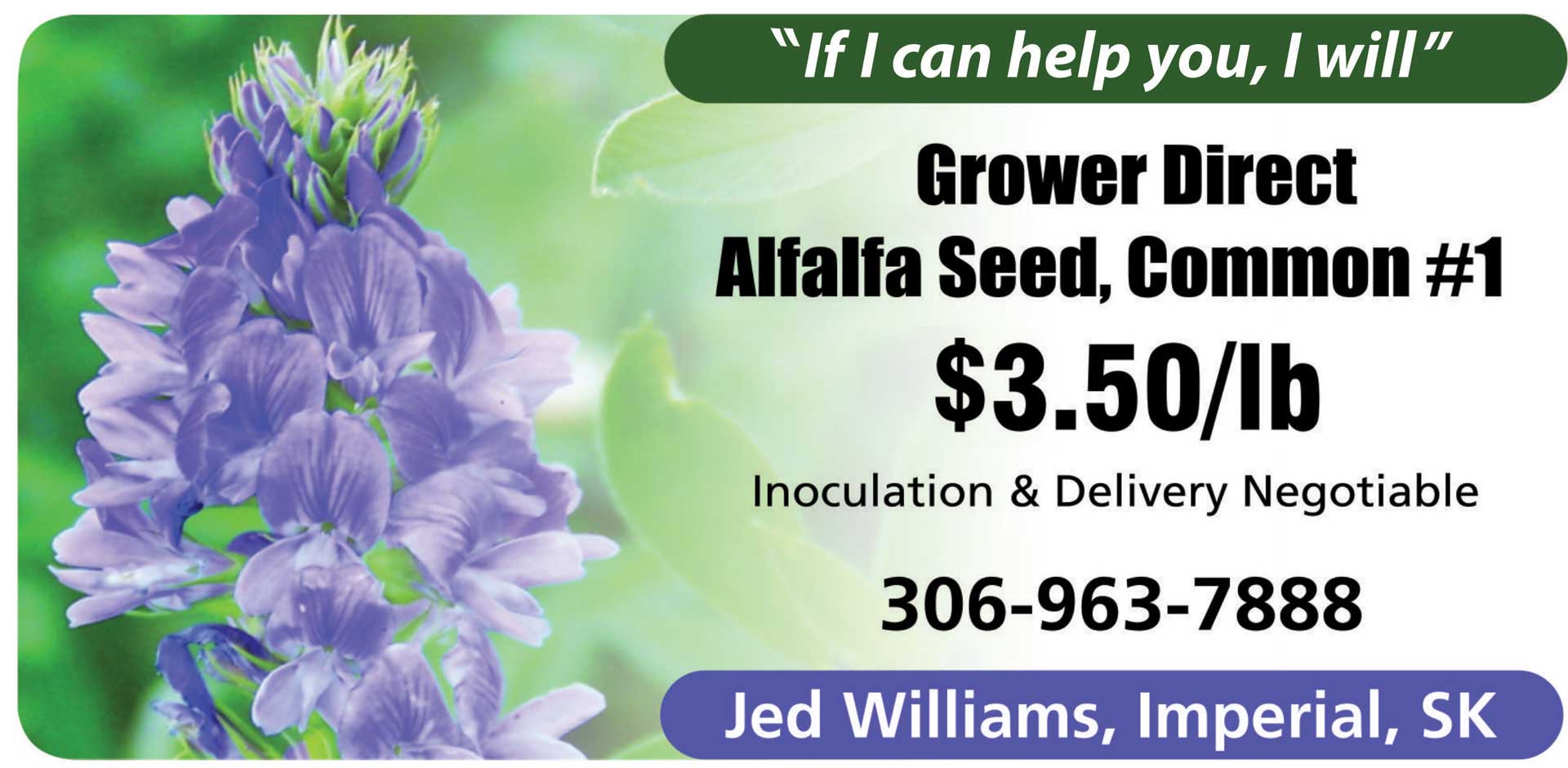

Unlike many alfalfa seed producers who produce under contract to large seed retailers, Jed and Kathy are independent producers who market their own seed.

They sell top quality, cleaned seed with delivery and inoculation negotiable.

When alfalfa markets went south in 2017, the couple had about 1,700 acres of alfalfa seed production.

In 2019, about two years after the market downturn, seed production on the Williams farm will be reduced to roughly 1,200 acres.

There are positive signs on the horizon.

Markets for alfalfa hay are strong and demand for Canadian alfalfa products is growing in overseas markets.

At the same time, North American alfalfa acreage is significantly lower than it was a few years ago.

When the market tanked in 2017, many contracted growers in the United States were forced to remove a significant portion of their acres from production.

Together, those factors could re-ignite interest in alfalfa seed, but the rebound won’t happen overnight.

“At the current time, the oversupply of alfalfa seed needs to get used up,” said Jed.

“Whether it gets exported around the world or put in the ground and seeded, the volume that’s out there needs to dry up a bit.”

This winter, in the midst of a flat market for bees, the Williamses will extract more than 100 million leafcutter bee larvae.

“You either sell them or fly them,” says Jed, a self-reliant operator who’s involved in every aspect of the business, from planting, harvesting and marketing seed to managing bee inventories and designing equipment and larvae management systems.

A while back, Jed and Kathy acquired the Imperial Town Hall, located on the village’s main street, as well as the community’s former meat market building, just a stone’s throw away.

The town hall serves as storage space for about 9,000 leafcutter nesting boards that are brought in each fall.

Each board contains thousands of bee larvae, which are extracted using a specialized punching machine.

Extracted larvae are sold by the gallon, typically to alfalfa seed growers in Western Canada or the United States.

Larvae that aren’t sold are retained by the Williams, incubated in the former meat market building and used as alfalfa pollinators.

Hatched bees are moved to the field in late June.

To manage their growing larvae inventory, Jed and Kathy have also started a sideline business — Backyard Pollinator — that sells leafcutter bee larvae into the hobby market.

Hobbyists, gardening enthusiasts and orchardists can buy pre-cut nesting board sections that contain 200 to 400 leafcutter larvae each.

Once they’re hatched, the bees go to work quickly, pollinating flowers, fruit trees, vegetables or anything else within their range.

Larvae sales into the hobby market have helped the Williams manage their inventory and increased awareness about the importance of pollinators, said Kathy.

Leafcutters are efficient pollinators but unlike other bee species, they are solitary and non-aggressive, she added.

Orchard operators that have used the bees to pollinate their crops have reported increased fruit yields.

“There’s a lot of people out there who are pretty fascinated by bees,” Kathy said.

Efforts to sell into the hobby market have been successful but have added another layer of responsibility to an already busy career.

Fortunately, Jed and Kathy are not the types to back away from a challenge. Their children, who pitch in on the farm, are learning similar values.

“The easy part about marketing is to sit on the couch and (whine) and complain when markets disappear,” said Jed.

“The hard part is getting off the couch, making the phone calls and finding the people who want your products.

“We’re 17 years into it now and we’ve learned a lot of the tricks of the trade the hard way.… But one day, my kids will be able to say, ‘Mom and Dad built a successful business and I remember when they first started out, we would sit together making seed samples at the kitchen table (for potential customers).”